This year I worked as a researcher for a priest who was interested in the role his grandfather had played in the pioneering of the sport of harness trotting in Western Australia in the early twentieth century.

My work involved reviewing digitised newspaper articles from the ‘Trove’ service offered by the National Library of Australia (http://trove.nla.gov.au). This service is truly something to laud, to cherish, and most importantly, to use; through its digitised records of newspapers from the early nineteenth to late twentieth century, we have access to the most intricate of details from the last two hundred years of our country’s social and political history. It is an online equivalent to microfilm rooms in State and National libraries, which are sadly only frequented by a small group of people, most of whom are elderly Australians in the twilight of their life looking into their genealogy.

As with so much of current education and knowledge, there is not a lack of access to information or existence of accurate information, but a lack of initiative in studying it. All Australians should take the opportunity to stroll through the archival museum of Australia’s past and the startling richness of their ancestors’ lives, which are captured and immortalised in the pages of these old newspapers. Such an activity encourages an appreciation for precedence, continuity and one’s place in history. We are privy now to more information about our ancestors than ever before, but most people cannot even tell you who their great grandparents were.

Reading through the newspaper articles, advertisements, and listings week after week, I was amazed at the stark contrast between the sort of reporting of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when compared to today’s papers. Our newspapers, especially traditionally broadsheet papers like the Australian, are considered by conservatives to be a dying cultural treasure, an opinion with which I largely agree, but when such papers are compared to those by which they are preceded, they pale considerably and it becomes clear that we do not only have to conserve our papers but restore them to their former glory.

Broadly, the newspapers of those times were grammatically above reproach, consistent, and comprehensive, the latter sometimes to the point of tedium. Newspapers viewed themselves as the watchful and interested eye of the public upon all the social, political and natural occurrences of community life, rather than just reporters of trends, global affairs, and memes.

Although large sections of newspapers were dedicated to making the views and opinions of public figures known as well as publicising community debates faithfully, newspapers were not dedicated to the competition of political agendas or the unashamedly skewed telling of one side of the story. The current newspaper market is so dominated by politics and opinion that it has become necessary to politicise reporting in order to counteract the influence of the ‘other side’ of reporting. Making conjecture and spin the substance of your newspaper is not the same thing as reporting from the stance of a particular school of thought. A wide and silent section of the community do not consciously subscribe to the sort of agenda and ethos as any of the newspapers or broadcasters but merely wish to be informed. This is an inherently moderate and reasonable attitude, the true origin of an open mind, and we should reward that attitude with objective reporting.

I have heard stories of newspaper editors refusing to report on particular people as ‘pro-life’ instead of ‘anti-abortion’ at their own request. The Australian will occasionally represent people opposed to same-sex marriage as ‘pro-marriage’ whereas the Sydney Morning Herald will report that such people are ‘anti-gay’ and to the Pink News you’re a fully-fledged ‘anti-equality campaigner’. These newspapers notably take polls on reports of current events, confirming that they are interested in seeing how well their pieces have done in shaping public opinion. Something even more likely to shape public opinion is the commentary sites such as the Sydney Morning Herald place beside ‘yes’ and ‘no’ options on these polls. On the recent newspaper poll 12/12/13 concerning whether readers approved of the ACT Same-Sex Marriage Law strike-down, they wrote “No: everyone has the right to marry the person that they love”, a neat little slogan to ‘inform’ people why they might want to vote ‘no’, and merely a tautological “Yes: it was the right decision” next to the ‘Yes’ vote rather than something like “Yes: it was an unconstitutional law” or “Yes: Marriage should be left to the Federal law”.

These blatant pieces of spin belong in the media strategy of politicians with obvious vested interests in public opinion, not reputable newspapers. The maxim that “objectivity is dead” is best responded to with the assertion that if objectivity is dead, the media has killed it. Morning shows and newspapers running campaigns on divisive issues and panels that churn through the same issues week after week teach the populace that the very people reporting on occurrences are also tasked to interpret them for us. This is not to say that newspapers should not run exposés, especially into situations involving gross miscarriages of justice or corruption. But it should be up to private citizens to form opinions based on the objective reporting that newspapers provide.

If reporting is filtered through an ideological lens, the only role the public has left to play is either to follow dogma or reject it, rather than render events into opinions in their own time and in their own way. The more comprehensively events are reported, the best able the public will be to make up their mind and develop a mind of well-informed political opinion based in fact. We should remember that opinion is cheaper to formulate than detail, and with the worship of efficiency taking hold of our society in recent times, we should be immediately suspicious of news sources more keen on filling their pages with trends and opinion rather than actual happenings around the community which would take hours of manpower, concentration and fine-tuned attention. Comprehensive blogs such as Rafe Champion’s “Rafe’s Roundup” contributions (http://catallaxyfiles.com/2013/12/05/rafes-roundup-6-nov/) provide a surrogate for this sort of close attention, and it will be interesting to see how the blog genre develops in filling such gaps.

I went to Parliament yesterday to observe its proceedings and there was only one news reporter in the media gallery. Granted, there were not that many members of parliament in the chamber either, but under review was failed infrastructure projects of the Labor government and infrastructure projects threatened with cuts by the incoming government – matters of some heat and much importance. By contrast, in the early twenty first century, every major newspaper in Perth reported in obsessive detail a Town Hall argument among the executive of the Western Australian Trotting Association as to whether its system of government ought to be altered to allow more control from the executive board and less from the board of guarantors. Exact transcripts were produced for the public to absorb and make up their mind upon. Imagine a society in which we all had such interest, not in each other’s midday meals or duckfaces, but the operations of our long-running public institutions, societies, and universities, such that every major newspaper in Sydney would publish a comprehensive report on the local RSL meeting, changes to regulations in Sydney University student associations, legal proceedings and the smallest of Parliamentary debates?

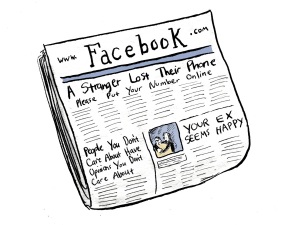

Another difference between today’s papers and those of the early twentieth century was the sense of community their papers both generated and reflected. In those days, people took locality seriously while also tracking the developments of the Anglosphere more generally. If you lived in Perth, you would read the newspaper in the morning because all of your friends’ movements and business ventures would be published in its pages – a bit like an old-fashioned form of Facebook. In some ways, as with all societal change, we haven’t discarded but rather imported the finer social detail of those newspapers onto an online medium; that of the social network. However, our social networks could be an artificial re-rendering of the sort of society that could be represented by a single paper in the past. Our population has ballooned so much and our society has become so diverse and disjointed that in order to satisfy our vague sense for ‘what is going on’ we check in with our 500-1000 Facebook friends to feel connected rather than read the newspaper, in which all the people mentioned we will hardly have met, unless we are part of the political elite. It is not the same story for local newspapers, but their readership is small and today they are all owned by Fairfax or News Limited, meaning that there is a top-down approach to local reporting, something that should surely be an oxymoron.

Back in those days, when a man of some note was on his deathbed, every major newspaper in Perth sought his state of health three times a day and published information concerning him every day. When he finally had his funeral, every single name of hundreds of mourners was published in the newspapers as well as a comprehensive account of the ceremony. Such was the extent to which people cared about the members of their community and wished to pay close attention to each other’s milestones via formal procedure, keeping each other at a respectful distance. This may be compared to the ‘selfie culture’ of the twenty-first century and the scant detail on people of interest in newspapers. What detail is published is inconsistent in that it is rarely followed-up and information loses what is crucial for it to be interesting: its sense of narrative and continuity.

The only problem with a proposed restoration to old methods is clearly that the culture of the readership has changed so much due to paradigm shifts in objectivity, a decline in literacy and vocabulary, and a technology-induced psychological need for immediacy and trends. This may be seen in the decline of readership of newspapers generally and the move from broadsheet to tabloid-style papers. I work for a company whose main duty to Fairfax is to distribute its newspapers for free. You’re more likely to see people with papers like the MX or their smartphone in their hands out in public rather than the day’s paper. If newspapers were to regain their prior nature, would the readership necessarily increase in size and retention? Would, perhaps, the readership fail to connect with that style of reporting and reject it wholesale? It’s up to us to decide, and to demand the sort of quality we are willing to reward with our money from the papers generations of Sydneysiders has sworn by for so long.

Related articles

- Do local newspapers have a future? (dpetrieblog.wordpress.com)

- News Corp’s Australian newspapers sees 22 per cent revenue drop (mumbrella.com.au)

- How to do comprehensive coverage (mumbrella.com.au)